The story of Coligny is the story of the tragic death of Faki Mosweu and the subsequent light that it shone on the raw wound that is South African race relations.

South Africa recently experienced overlapping waves of protests, perhaps the most prominent of which was centered around the small farming town of Coligny. Coligny is a small, mostly unremarkable, rural town, the likes of which are scattered across the South African countryside. You’d be forgiven for not having heard of it before it entered the national zeitgeist for tragic, violent reasons.

Earlier this year, in late April, (mainly black, poor) residents of the town took to the streets in violent protest after two white farmhands who are accused of murdering a 16-year old teenager named Matlhomola ‘Faki’ Jonas Mosweu were granted bail. Mosweu, who was reportedly hungry, was caught stealing sunflowers by the farmhands. Residents took to the streets to protest what they considered double-standards of justice for black and white South Africans.

Accounts of what happened after Mosweu was apprehended by the farmhands diverge. Depending on who you believe, Mosweu was either violently tossed from a moving vehicle causing him to break his neck and die at the scene, or he jumped from the vehicle of his own volition to escape the farmhands handing him over to the local police for a light slap on the wrist, as was the farmhands’s modus operandi with the several previous youths that they had caught stealing sunflowers apparently.

At the same time that protests erupted in Coligny, others flared up in Johannesburg relating to service delivery (spreading across Eldorado Park, Finetown, Ennerdale, Lenasia South and Kliptown, amongst other areas), and yet others relating to a long-standing dispute over municipal boundaries reignited in Vuwani in Limpopo. However, these protests, while still receiving significant coverage, were eclipsed by the events that occurred at Coligny. South Africans have a sadomasochistic gluttony for race rows, which the violent, tragic events of Coligny delivered in spades. Protests over ‘prosaic’ matters such as service delivery stood no chance in comparison.

The data

I started collecting data about the various protests around the time that the Johannesburg protests kicked off. I collected about 44,000 tweets relating to the topics of Coligny, Vuwani and the Johannesburg protests between 8-22 May 2017. The Coligny events had already been unfolding for a week or two by this point so these volumes are not a good indication of the overall number of tweets generated. Similarly, the Vuwani protests have been going on intermittently for about two years now, so this data just captures part of the latest flare-up. Given these caveats, below is what the volume of tweets relating to each protest location looked like. Discussions around Coligny clearly dominated:

The specific events of this dataset – Coligny, Vuwani and the Johannesburg protests – almost seem like old news now given the speed with which the news cycle hurtles forward (#GuptaLeaks anyone?). However, I thought it worth writing about because it represents a unique view into our nation’s wounded psyche.

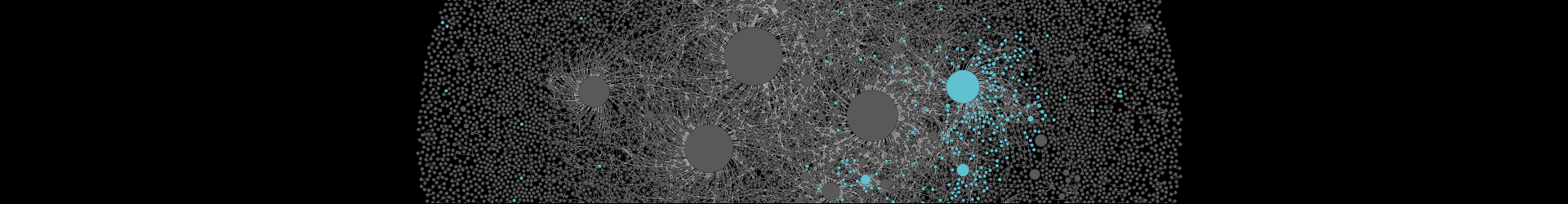

This dataset is unique because it includes a prominent community of conservative (for lack of a better term), white South Africans. South African Twitter is dominated by black South African users (as are most aspects of South African life considering that 80% of the population is black), although white South Africans do still have a notable presence on Twitter (these users tend to be more of the liberal persuasion though). In this dataset, we find that conservative-leaning users were more vocal than usual, likely as they felt uniquely threatened by the events in Coligny.

Coligny is a microcosm of the dynamics at play in many parts of rural South Africa. It highlights the tension inherent in much of our country – a hangover from apartheid where few social dynamics have changed fast enough. The narrative was cast from the get-go as one of black (poor, landless and hungry) versus white (land-rich and insensitive to the plight of their neighbours). The reality is complex due to historical inequalities which have lead to persistent, structural economic differences between races which, when combined with a generally depressed local economy, create a situation ripe for conflict.

Coligny bares the wounded South African psyche

The two sides of the race coin were perhaps best captured by a series of editorial articles spurred on by author, Rian Malan’s, initial write-up of his visit to Coligny, where he suggested that the white farmhands had precedent to backup their claim that Mosweu jumped from their bakkie, that there was no real evidence to support an alternative interpretation (including dismissing an eyewitness account that, if true, tells a very different, reprehensible story), and that the other real, unrecognized tragedy was that foreigners bore the brunt of locals’ anger (implying undertones of xenophobia).

Many responded to Malan’s interpretation of events. Professor Nicky Falkof from Wits University highlighted problematic aspects of Malan’s choice of metaphors and wordings, implying that they were based on a deep-seated racial paranoia that was a hold-over from the ‘swart gevaar‘ thinking of the apartheid era.

Sisonke Msimang admonished Malan for shifting the story from the tragedy of a young man’s life snuffed out within a deeply unfair system that perpetuates such tragedies amongst the majority populace to the anxieties of Coligny’s minority white populace and, indeed, Malan’s own. Malan responded to Msimang in turn, making no qualms about the paranoia he felt as a white South African over the whole situation.

Taken together, these editorials sum up several different perspectives on South African race relations. These perspectives were further echoed on Twitter where many communities weighed into the various discussions. The below chart highlights the top ten communities discussing the various protests:

The chart below summarises the largest and most vocal communities. Each community is represented by a bubble, the size of which tells us what proportion of the users fell into that specific community in our dataset. The position of the bubble tells us how many users were in that community (x-axis) and what proportion of tweets came out of that community (y-axis).

Communities that sit above the diagonal line in the below chart produced a greater proportion of tweets than we would have expected given their size. This is usually an indication of a particularly passionate community that is generating a lot of heated discussion.

The Conservative white community, which was the second largest community, clearly stands out as the most vocal given its size. This community seldom appears in the data that I analyse around major political events and it is their presence here that prompted me to write this article in the first place.

So, what we have here is a community that largely keeps to itself when it comes to public discourse, but which has been thrust into the limelight due to the nature of events. Are they particularly vocal perhaps because they feel threatened by the events in Coligny or, perhaps more existentially, by the implications for white South Africans’ place in South Africa? Or, maybe they are all just racists who can’t let an opportunity that confirms all their existing beliefs about black South Africans pass without spewing racist vitriol? Again, the reality is probably more complex than either of these scenarios in isolation…

To start unpacking these issues, let’s isolate the most retweeted content that was generated within three communities in particular to get an idea of the worldview and narrative each was working under during the tragic events surrounding the Coligny unrest.

Black Twitter’s response to Coligny

Let’s start by looking at the single largest community; what is commonly referred to as Black Twitter (even though this is a woefully inadequate label to represent the diversity of views contained herein; if you have any better suggestions, please let me know via the Superlinear Facebook page).

Overwhelming sadness and anger were the main responses from this community; sadness at the perceived lack of value given to the life of a young black South African, and anger at the double standards with which the law is perceived to operate for black and white South Africans. Many parallels were drawn between the way Fees Must Fall activist, Bonginkosi Khanyile, was treated in custody versus the two murder accused, showing how the events at Coligny were seen within a wider national context:

A black child was murdered over a sunflower by white men who refuse to see black life as having any value.

And they got bail.#Coligny

— Pandahoenium* (@PearlPillay) May 8, 2017

A black child was murdered by 2 white racist men. Because of a sunflower! And now they've been granted bail. The fuck. #Coligny

— Azra Karim (@AzraKarim) May 8, 2017

Why are whites always innocent till proven guilty but blacks guilty till proven innocent? #Coligny

— Naledi Maleeme (@nals14) May 2, 2017

#Coligny

He was in chains yet this 2 are not in chains and he was denied bail the 1st time around. pic.twitter.com/iylQGgYjCP— #Maftonian Ninja (@kcshupsta) May 8, 2017

Assasin accused – R3000 bail

Farmer murder accused – R5000 bail

Student activist – Denied bail and had to appeal.#Coligny Elvis Ramosebudi— Bulelani Phillip (@BulelaniPhillip) May 8, 2017

The conservative white community reacts

As already touched on above, the conservative white South African community usually keeps to itself on Twitter (or at least they keep their debates amongst themselves). Liberal white South Africans tend to enter the debate more often. However, this was a rare moment when this community became particularly active. Unsurprisingly, their take on the Coligny events was very different. Where some commentators saw violence, they saw self-defense (as in the case of the scuffle between the journalist and farmer below); where some saw biased interpretations of the law, they saw institutions doggedly sticking to the rules rather than buckling to populist pressure; and, most clearly, they saw persecution of their community due to their race.

"Journo attacks farmer before gets KLAPPED"

#Coligny @eNCA or enANN7 pic.twitter.com/gkFaQYphME— Ian Buyers (@IanBuyers) May 8, 2017

Hate Crime: #coligny rioters burn down farmer's house because he is white. He had nothing to do with the trial. #HateCrime https://t.co/aaHIdzEEWx

— AntiHateCrime (@HateCrimeSA) May 8, 2017

#coligny more blacks has killed blacks in this past week then white on black crime… remember that aswell while u burn down ur town

— #OurGirlsAreMissing (@ChesterQha_) May 8, 2017

An eye for an eye will leave us all blind. National leaders please step in to ensure reconciliation while justice takes its course #Coligny https://t.co/vecEQFRtt0

— Adv Thuli Madonsela (@ThuliMadonsela3) May 8, 2017

#Coligny: Magistrate explains law why state can't lock up people, on weak evidence, just because of mob rule, in hope ignoramus understand. https://t.co/6KoN4jjObc

— Graham Robert Evans (@cliviagraham) May 8, 2017

The Radical Economic Transformers and rent seekers’ enter the fray

This community often makes me scratch my head. While there is nothing overtly wrong with ‘radical economic transformation’ – indeed, it’s a laudable and very necessary goal in our country – this group of ideologues has woven such a complex web around concepts of black empowerment and personal enrichment through rent seeking that they have undermined the nobility of their cause. It’s an important community to track as their worldview has been adopted and pushed within government by the Zuma faction and through more nefarious means such as the underground PR machinations devised by Bell Pottinger (see here, here and here, for example).

To understand how the goal of radical economic transformation was incubated and subsequently diverted by vested, rent seeking interests, I highly recommend reading the Public Affairs Research Institute (PARI) report on state capture. It puts this community into context and is a very accessible read.

Here then is the content that resonated most with this community, including welcoming the prospect of a revolutionary apocalypse in order to rebuild a new, black utopia.

The Magistrate who granted bail to the RACIST murderers in #Coligny enjoying beer.

Was the granting of bail sealed at the bar? Sad! pic.twitter.com/XkOPJ79rVT— Sine Themba (@savethebay4) May 9, 2017

#Coligny shows what I always warn. South Africa is an explosive keg, a civil war can easily start, White racists must stop killing blacks.

— Bo Mbindwane (@mbindwane) May 8, 2017

#Coligny S.A. shall burn and from its ashes shall rise Azania. We getting there.

— andile (@Mngxitama) May 8, 2017

On the other hand I don't trust racists. They could easily have caused arson on their houses for insurance purposes. #Coligny

— Bo Mbindwane (@mbindwane) May 8, 2017

A twitter user said “if Mosweu’s family had land, then he would be picking sunflowers in his own backyard. And still be alive.” #Coligny

— BLACK 1ST LAND 1ST (@Black1stLand1st) May 9, 2017

What do we take out of this brief journey through the South African psyche? As usual, I don’t have any answers or incisive insights. Instead, this article has simply described several different angles on the way South Africans reacted to complex events and dynamics.

I don’t expect you to leave this article with a changed perspective but hopefully, by highlighting several perspectives, we are all in a better position to integrate the Other’s point of view to evolve towards some kind of common conception of nationhood and brotherhood/sisterhood. We are all in this together after all…

Hi Kyle

This is really interesting, thank you. I have some questions about the methods you used:

1. What criteria did you use to choose these ten communities?

2. These communities appear to be mutually exclusive – is this correct? If so, surely many of Simamkele’s re-tweeters, for instance would also identify as black twitter?

3. What process did you use to code all these tweets into the ten communities?

Hey Nimi. The communities are identified using the Louvain modularity algorithm. It is a statistical technique that looks at the relative density of connections within and between groups, and tries to find the best place to draw a boundary between groups. It is a mutually exclusive approach although there are other community detection methods that allow a node to fall into multiple communities. Mutually exclusive is usually fine in most circumstances where the data relates to a well-defined topic since people seldom hold multiple views on the same issue, but when looking across different topics, multiple community memberships can make more sense (e.g. I might love cars and fashion and so would want to appear in both communities). The modularity algorithm has a default parameter for identifying community cut-offs that can be tweaked. It’s important to remember that these are rough allocations with fuzzy boundaries and so should be taken with a pinch of salt, especially for the members on the edge of the community.

In the case of @simamkele, often times when a specific user’s tweet goes viral, the algorithm will identify them as having their own “community” due to the large number of people that retweet them. This is an artifact of the data and, based on a qualitative evaluation of the user/community involved, you could probably combine them into the same community.

Given the above, we don’t “code” the tweets into communities. We map a network of interactions between users and let an algorithm decide what the communities are that users fall into. The researcher’s involvement is to give these communities names based on what they are (re)tweeting, who the main influencers are, etc. and this is an admittedly subjective process.

Hope that helps 🙂